The Dollhouse Economy

Fairy tales, material literacy, and the joy and necessity of making

“It may be that when we no longer know what to do

we have come to our real work,

and that when we no longer know which way to go

we have come to our real journey.

The mind that is not baffled is not employed.

The impeded stream is the one that sings.”

-Wendell Berry

I do not inhabit the realm of fairy tales.

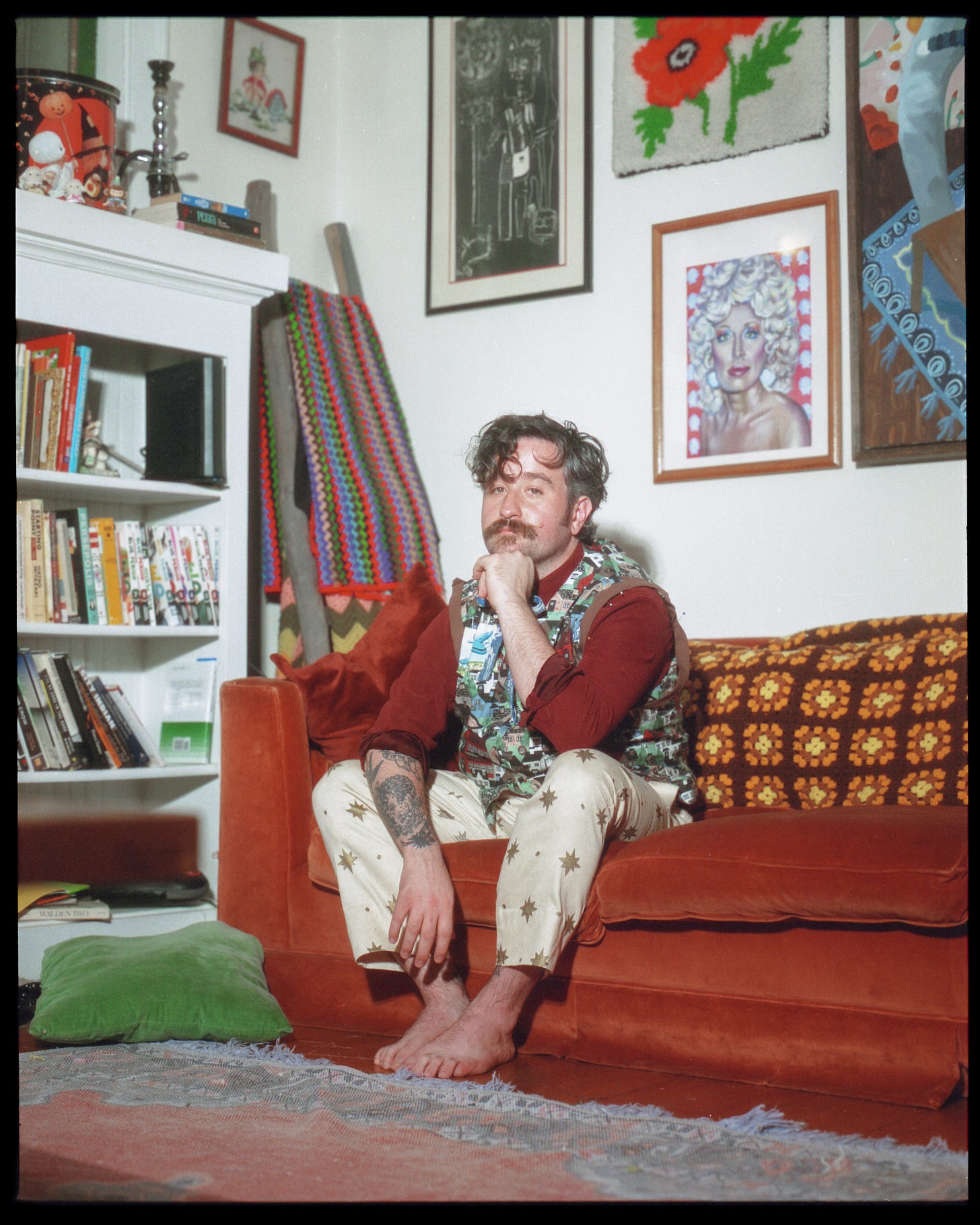

No birds hang my laundry on the line, and no tiny women emerge from my pomegranates to finish my housework. Though I often write myself at the scale of a dollhouse, I regret to inform you that I am merely a slightly-below-average-sized man.

My house is human-sized, too. It stands on a block in a neighborhood where gun shots are sometimes heard, with police sirens and car alarms in the nightly chorus. No, I do not live a fairy tale—but fairy tales, too, are ruled by malevolent forces. Arrogant monarchs, scoundrels, and monsters fill the pages of the Brothers Grimm as surely as they haunt everyday life.

If we look closely at what we are taught not to see, we soon find that the mechanisms of modern existence are ruled by fairy tale logic. We live in a world where information and products are instantly and infinitely available to us. On the surface, this has become accepted as a fact of reality, but these things always come with a hidden cost.

Everywhere we look, there are Amazon vans stamped with the slogan Everything and the Kitchen Sink: Delivered! As I type, there are millions of hands clicking a mouse, adding everything-and-the-kitchen-sink to their shopping carts.

We act as though we live in an Edenic paradise, believing these conveniences are morally neutral—but they are not. With every click, a chain of events is set in motion. An uninsured, sleep-deprived worker in a warehouse picks, packs, and labels everything-and-the-kitchen-sink. Our orders pass through a long succession of hands and onto a van with a sleep deprived driver, who races against the clock to meet ever rising daily quotas on the way to our houses.

From my desk, I watch the van pull up to my house every day to deliver to my upstairs neighbor. On average, there are three new boxes each day. I often hear a great deal of racket above me, which must be related to the management of this continuous flow of new inventory. Every day I hear her hauling deliveries up the stairs, breaking down boxes, and back down to discard the cardboard by our dumpster.

I would like to invite my neighbor down to my apartment to read a fairy tale. I think I would choose The Elves and the Shoemaker—a tale of an impoverished shoe maker who had only enough leather to make a single pair of shoes. After prayer, he awoke to a perfectly completed pair of shoes. He sold the shoes, enabling him to purchase more leather. After making his cuts, he left the leather on his workbench and awoke to another perfectly cobbled pair of shoes. One evening, the shoemaker decided to stay up overnight to see who was doing his work for him. He found two tiny, naked men crafting the shoes and running away once their work was done.

In the tale, the shoemaker and his wife decide to thank the elves by crafting them tiny clothes and shoes. Of course, in our apartment building there are no elves, but there are amazon delivery personnel who go unseen, delivering us many things which we bury ourselves under in the futile hope of satisfaction with our lives. We are never satisfied, and the workers trudging through the snow with holes in their shoes never get a reprieve from delivery quotas.

Fairy tales help us to see what is unseen. We find ourselves enmeshed in web of exploitation, with ever increasing complexity that we have no shared language to describe. Fairy tales have proven to be a surprisingly effective framework to map this web. They offer us a vision of what it could mean to live in community with each other, using craft not only as currency, but as a means of reciprocity. Although they might seem whimsical, fairy tales show us that a collective return to craft could help us transcend consumerist narratives and regain power over our own personal narratives.

Do you inhabit the realm of fairy tales?

On a symbolic level, I believe we do. If read at on a surface level, these stories are dismissed as frivolous, fantastical stories only meant for children. However, revisiting these stories as an adult, I find that they are quite useful in subverting narratives imposed by imperialist, capitalist power structures.

Fairy tales are not what Walt Disney would like us to believe they are. They are not meant to be revisited nostalgically. They are the stories of the peasantry, passed down orally through generations to offer protection against exploitation and served as a warning against the pitfalls of greed, the abuse of power, and deception. If we ask ourselves what storytelling traditions are alive in today’s peasantry, we rarely see narratives that compel us to create for ourselves, but to only consume. Our aspirations themselves no longer belong to us, but are harvested as data to create advertisements to sell us a dream dreamt up by marketing firms.

When the Brother’s Grimm wandered the countryside collecting tales from spinsters, these tales were at risk of being lost to time forever. In their original context, these stories were told around spinning wheels. With the invention of the spinning Jenny and textile mills, this craft left the home, and spinners and weavers entered the mills. This severed a thread as old as time: the connection between craft and storytelling.

And so, the men who owned the textile mills became our story tellers. The working class lost control of their own narratives, and their most deeply held beliefs about their position in the order of the world and what it meant to live an agentic life were corrupted and colonized.

Yet, in endless copies of The Brothers Grimm that lie around attics across the world, these stories remain. We believe they no longer make sense in our context, but I insist that they do. In my study of fairy tales, I’ve picked out a thread that runs through all of them: knowledge of the earth and its materials, and the ability to transform them into a finished good.

The protagonists in fairy tales resist their oppressors in countless tales through their crafting skills alone. While the circumstances in fairy tales are exaggerated with magic, the central moral of these stories is quite simply achieved in reality: learn a craft to become self sufficient, and no one can own you.

“Resistance” is at the forefront of the collective vocabulary lately, but how exactly do we plan to resist if no one understands the world’s materials and the processes required to turn them into useable goods? How do we expect to achieve liberation while expecting invisible people across the supply chain to make all of our things for us? How did we become so uncurious about the mechanisms of our own survival? I would say the obvious answer is capitalism.

Capitalists spun the narrative that labor is separate from daily life. We now live under an illusion that we can all together transcend the tedium of spinning, weaving, sewing, baking, and growing food simply by typing our debit card numbers. Somehow, we think that by alleviating ourselves of any responsibility to each other, we will reach a state of eternal bliss.

Rather than bliss, we live with a dull and persistent anxiety that our lives no longer belong to us. It may be that we do not know what to do, but could this mean we’ve finally arrived at our real work?

Fairy Tales and Material Literacy

Material literacy preceded textual literacy, grounding individuals in their environments with knowledge of the earth and its materials. Creativity was once inseparably linked to the concept of home and self. As the objects surrounding us in our homes become increasingly uniform, mass-produced, and detached from their origins, so too do we lose touch with our own sense of identity and continuity with the past.

An active engagement with the past is imperative to reimagining a future. I do not offer a sanitized, nostalgic view of the past—I’m not naïve. Yet, when I highlight its benefits, I'm dismissed as overly romantic, while those who uncritically embrace a pixelated, dissolving future are hailed as logical. Do I inhabit a fairy tale, or do they?

We of the peasantry need fairy tales and story tellers. We need to become curious about our material reality, and become personally invested in it’s creation—even in the smallest of ways.

I do not propose that everyone is to become a master craftsman overnight. I do not believe that is everyone’s calling. I do believe that small shifts in perspectives and a small commitment to patching and darning our clothes could be a good enough of a start.

I often do not know what to do but to make. I know that it is a great privilege in such a world to have the time, knowledge and resources to make. Surrounding myself with handmade items, I spin myself into a cocoon of domestic comfort, creating space for my imagination to emerge amid the chaos of the greater world. This extra layer of insulation is new to me, and I know through my own experience that what I physically stitch, mends what is fragmented within me.

I do not inhabit the realm of fairy tales. I know that what I speak of here is real, arduous work. Work, however, when done to serve our own well-being and to care for others, is joyful work. This severance between work and daily life is a thread spun by forces beyond us—but fibers can be picked apart, carded, and re-spun into new yarn. So too can we unravel what is worn in ourselves and spin it back into something whole.

I'm excited to find your publication and the concept of "material literacy"! This is a theme running through much of my life's work (I studied eco-design and went on to co-found initiatives that attempted to revitalise material culture and making skills in various contexts – https://www.remakery.org/, https://arkforiraq.org/en/). There's a lot to unpack in the ways that culture traditionally was rooted in place / land and the materiality of particular locations... and the interrelation of story and metaphor with what people experience(d) through making with our hands and knowing places in embodied ways. I find it alarming how this huge layer of what it means to be human has been removed from our consciousness by having so much that is manufactured for us in places and ways we have no direct experience of. Thank you for naming and exploring this. Would be grateful if you can share any more about the origins of the term "material literacy" - did you invent it or find it?

“The protagonists in fairy tales resist their oppressors in countless tales through their crafting skills alone.”

Yes indeed. There’s a reason why the word “crafty” has a dual meaning, suggesting both “good with making” and “wide and cunning.”

It’s interesting that you mention the hidden costs of convenience and outsourced craftwork. I find the opposite is also true—bringing the tangible goods and the act of making back into the home creates benefits that are very hard to anticipate until they’ve been tried.

Very well thought-out as always.