In painting and drawing, we are taught to carve out the forms of our subjects from their surrounding negative space. I am finding that this is much the same with the medium of language.

I often draw my partner, David, as he reads. Sometimes, when he is crocheting. With pen or pencil, I carve his shape out of the couch or bed. I trace the lines of his fingers as they grip the book or crochet needle. There’s a certain way that his brows furrow under the frame of his glasses when he reads that I can never get quite right, but I try and try again.

It has been said that every work of art is a self portrait. When I sit opposite of David and draw him, I am, in a way, drawing myself. My consciousness becomes singular with the shapes his fingers make in between stitches. I am at one with the satisfactory “Mmmmm” sound he makes when he comes across a line of text he is compelled to underline. This is a signal for me to ask about what little nugget of wisdom he stumbled upon, and he’ll read it aloud for us to dissect together.

I could not reach this state of pure being if I were to look into a mirror to observe and draw my own face. I would become too fixated on the accuracy of the proportions of my jaw to my mustache, or to knowing the right expression to make into the mirror—somber, exuberant, or aloof? None seem to fit. I do not wish to be pinned down.

Instead I turn my attention outward, towards the image of David reading. This scenery is ever present in my idle time, so it seems like an obvious choice of subject matter. I do worry, though, do I pin him down instead? He is also a human being that contains multitudes, being many things to many people. But for me, he is always on our couch reading.

Perhaps I am getting too close to my subject. So quickly into the painting of the painting or writing of the essay we forget our initial intent. We obsess over our existential quandaries and find ourselves depleted before we can begin our creative work.

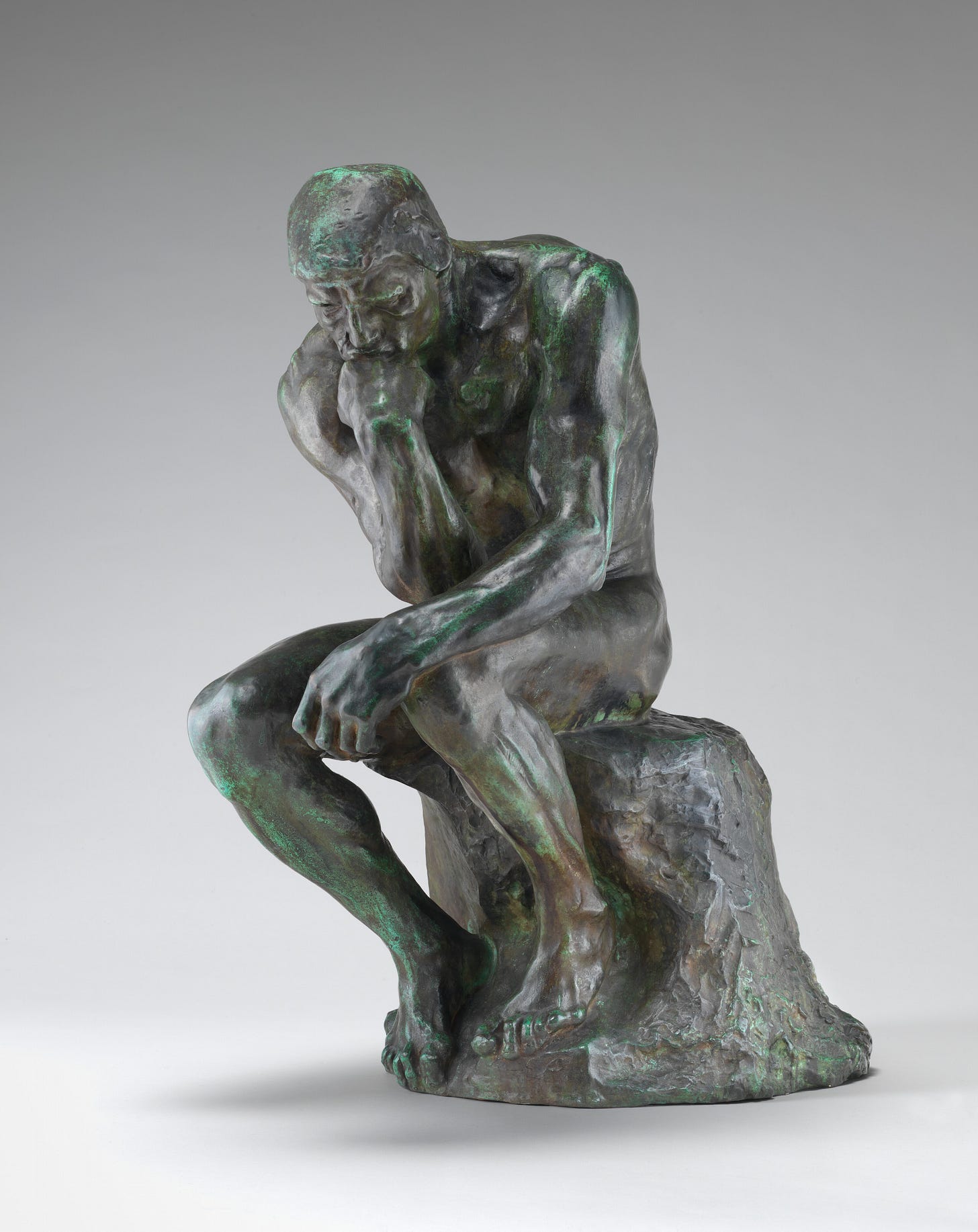

If I examine the negative shapes of this motif, I think it may be possible that what I’m drawing isn’t even David—I am rarely that concerned with capturing his likeness. Perhaps I am attracted to this image as a representation of the archetypal thinker, such as the one depicted in this sculpture cast by Rodin in bronze one hundred and twenty three years ago.

The Thinker has eternally set his gaze inward. His focus is unwavering. As demonstrated by the patina creeping across his surface. The Thinker eternally ponders the opposites: life and death, good and evil, freedom and captivity, truth and deception. In the same way, David sits statically on our couch, reading Dante, Morrison, Proust, and Dostoyevsky, as I watch the seasons change in the windows behind him.

Around the three year mark of our relationship, we looked at the life we’d made together thus far and knew all there was to know of each other. The ways in which we narrated our lives and experiences erected a boundary between us. We began the demolition of this great wall on the day that David went to the library and selected Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” on a summer day. As laid on the living room floor and read passages aloud to me, our ennui dissolved into Whitman’s prose.

“Have you reckon'd a thousand acres much? Have you reckon'd the earth much? Have you practis'd so long to learn to read? Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?”

-Walt Whitman

Reading Whitman, we hear his siren song for the beauty and simplicity of life, slipping away in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Reading Leaves of Grass in that moment resurrected something long dormant in me. This awakening led to the redirection of my attention, away from the 24 hour news cycle so that I could get closer to what is real and precious in my life.

There are malicious forces out to co opt our attention, and without our knowing, distract us from what is most precious to us. Both reading and making art serve to insulate us against these forces.

Artists today are unsure what to put in their pictures—It has all been done before. I would suggest that we begin with what is immediately around us. Pick one or two subjects as an object for daily devotion. Be present with it. Do not be concerned with rendering the subject faithfully. Allow yourself to become one with it.

I regret that I didn’t begin this practice many years ago—before having a partner or an aesthetically pleasing home as my subjects. Neither of those things, nor expensive supplies are necessary to begin. What is important in our art is that we cultivate our capacity for deep presence and lucidity.

“It has all been done before”. I would have to strongly disagree with this sentiment (Which I know you aren’t promoting). I feel like the art we desperately need is the everyday, the mundane, the struggle, the survival of those who are too busy and too hurting to make art. Those who have no money, no nice things. Those who have too many children and no help. Those who are in prison, on the hospital bed, or making another raunchy video to help pay for childcare. The “art” we need is truth-telling from the under privileged. The ones dismissed and erased. I feel like we will never get to a point in our society of “enough” art. We will only keep trying to allow those with something to say, the freedom to say it. I have so much privilege to have time to think…just coming out of 16 yrs of full-time child care. The fact that I can even sit here and respond is a huge ass luxury. It feels daunting to have time. Which problem within myself and outside myself should I look at? Which area of suffering do I have time for? I feel frantic!

I'm so torn over the feeling that I need to write after reading this gorgeous piece or the feeling that I should paint after reading this gorgeous piece full of gorgeous art. Such a lovely post! Thank you for sharing your thoughts.